It’s been almost one year since I built my first Microservice and one thing that I’ve been meaning to write about is the necessity for an application to handle graceful shutdown.

Initially, I didn’t understand why an application needed to be gracefully shutdown because I didn’t understand it in the context of a distributed system. In my primitive mental model, a web app was something deployed in a single box, traffic would funnel in, requests would get served (or not), and that was the end of it. Fault tolerance, reliability, and resilient architecture were new concepts that I was exposed to as I was building. Specifically within a Kubernetes environment, graceful shutdown is key to ensuring:

- Data Integrity and Consistency -> The state between app shutdown initiation and app shutdown should be accounted for in a reliable way (ie. in flight requests).

- Resource Cleanup -> Properly closing our app server, closing db connections, flushing our logs/metrics agent, etc.

- Zero Downtime Deployments -> Rolling updates allow a seamless end user experience as traffic will continuously be served while deploying new features and updates.

Quick Detour into Signals

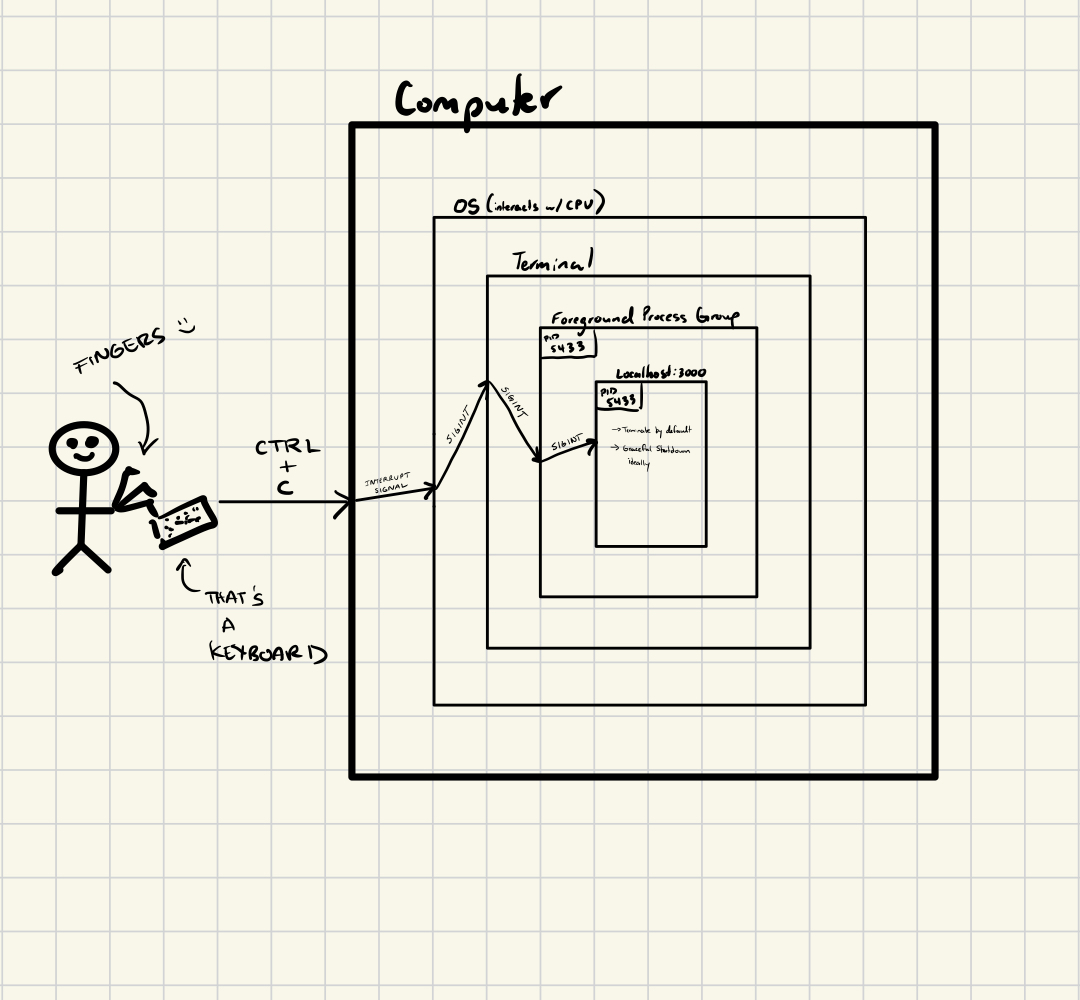

When thinking about terminating processes, I immediately think of CTRL + C. This command generates an interrupt , which the OS, in tandem with the CPU, interprets and sends the SIGINT signal to terminate the process.

Here’s a high level image of what’s going on when sending CTRL + C to a terminal window that has a server running on localhost:3000 (pardon me if I missed any key layers here).

The above is for a simple locally hosted web-app. In a production-grade containerized application deployed on multiple EC2 instances and living across multiple Kubernetes pods, graceful shutdown is paramount. Kubernetes pods can terminate for various reasons such as:

- Updating or Rolling Deployments (ie. terminating pods with older version of the app)

- Scaling Down (ie. going from 10 to 5 pods)

- Resource Constraints (ie. reaching peak CPU/Memory)

- Node Failure / Maintenance

- Health Check Failure

- and more!

Any of the above scenario would result in our application terminating and we need to ensure that the application shuts down cleanly; completes any in-flight requests, save necessary state, and not disrupt service to users.

K8’s Pod Termination

Kubernetes orchestrates pod termination in 3 phases:

- It starts by sending a

SIGTERMto the pods. This signal politely asks a program to terminate. - After sending the

SIGTERM, K8s kicks off a grace period (defaults to 30 seconds, but can be configured). Your application should handle theSIGTERMsignal and complete any remaining requests / cleanup operations within the giventerminationGracePeriodSeconds. - Once the

terminationGracePeriodSecondsends, K8’s will forcefully shutdown the pods via sending aSIGKILL, which would terminate the pod without allowing any further cleanup.SIGKILLcan not be handled or ignored by your program.

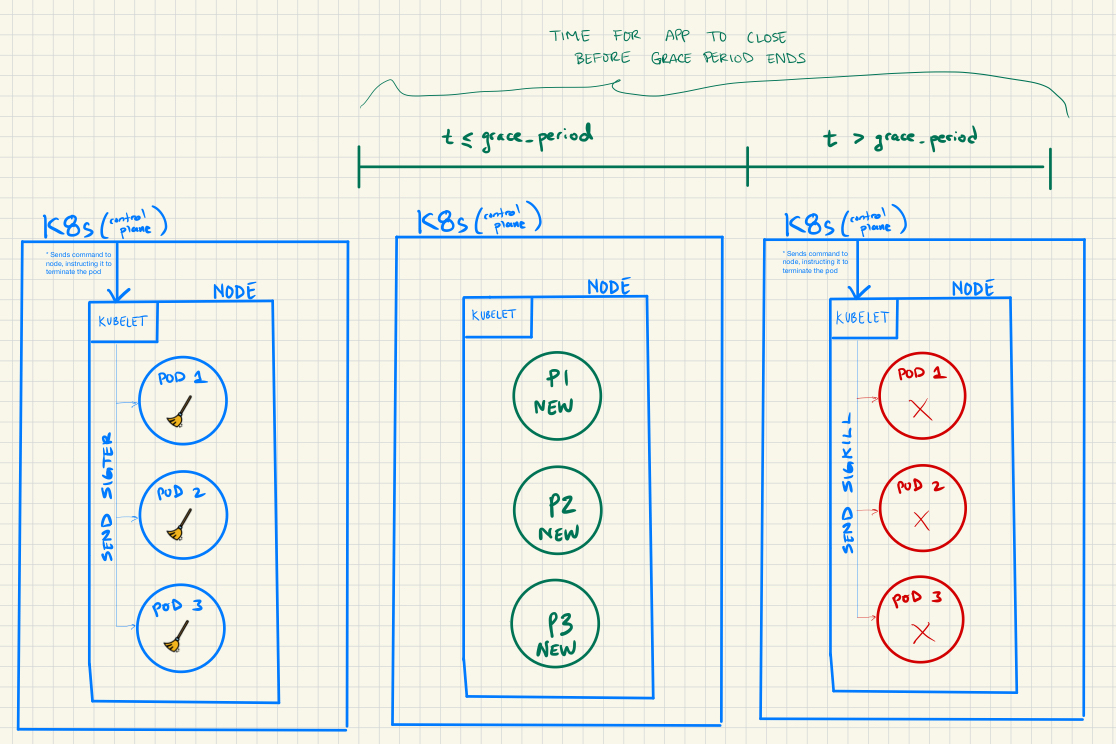

Here’s a high level overview of the application termination process in K8’s:

K8’s has a control plane, which can be thought of as the brain that manages the resources at a cluster level. The termination signals initiate here. Zooming in, K8’s also has the concept of a Kubelet. Continuing with the brain analogy, the Kubelet can be thought of as the peripheral nerves that carry out commands of the control plane at the Node level.

Once the Kubelet receives the SIGTERM, it sends it to the Pods and your application should handle it by perform any clean up operations. If the application shuts down before the terminationGracePeriodSeconds then the old pods will be deleted and new pods will be spawned. If the application does not shut down before the terminationGracePeriodSeconds then the pods will receive a SIGKILL and be forcibly shutdown. This will also delete the old pods and spawn new ones.

- Note that during the time between the forced shutdown of the app and respawning of new pods, incoming requests from the client will be met with unexpected errors (ie. connection failures, timeouts, service unavailable, etc.)

Graceful Shutdown Implementation

The implementation of graceful shutdown varies by programming language and framework. In languages such as Python, Ruby, and JavaScript, graceful shutdown is implemented in a seemingly “sequential manner” since their concurrency model differs from a language like Go. Moreover, using a well known web server framework may actually handle graceful shutdown for you.

This may seem like an obvious point, but it was a distinction that further developed my understanding of Go’s concurrency model.

Here are some VERY SIMPLIFIED example implementations:

JavaScript -> Signal is handled by Event Handlers

const express = require('express');

const app = express();

const db = require('./db');

const PORT = process.env.PORT

app.get('/', (req, res) => {

res.send('Hello, World!');

});

const server = app.listen(PORT, () => {

console.log(`Server is running on port ${PORT}`);

});

process.on('SIGTERM', () => {

console.log('SIGTERM signal received: closing HTTP server');

server.close(() => {

console.log('HTTP server closed');

db.close(); // Close database connection

// other cleanup tasks

process.exit(0)

});

// handle scenario when it takes too long to close connections / cleanup

setTimeout(() => {

console.error('Could not close connections in time, forcefully shutting down');

process.exit(1);

}, 10000);

});

Ruby -> Signal is often handled in the main execution thread

require 'sinatra'

require 'sinatra/activerecord'

set :database, "sqlite3:example.db"

get '/' do

"Hello, World!"

end

Signal.trap("TERM") do

puts "SIGTERM received, shutting down gracefully."

ActiveRecord::Base.connection.close

exit

end

Python -> Signal is handled in the main execution thread

from flask import Flask

import signal

import sys

app = Flask(__name__)

db_connection = connect_to_database()

@app.route('/')

def hello_world():

return 'Hello, World!'

def graceful_shutdown(signum, frame):

print("SIGTERM received, shutting down gracefully.")

db_connection.close() # Close database connection

sys.exit(0)

# Capture SIGTERM

signal.signal(signal.SIGTERM, graceful_shutdown)

if __name__ == '__main__':

try:

app.run()

finally:

db_connection.close() # Ensure connection is closed if app exits

In all these examples, we observe the sequential nature of the written code. In technical terms, the main execution thread is usually responsible for catching the termination signal.

In Go, however, we have the flexibility to create a separate goroutine (lightweight thread of execution) that listens for signals via channels. There’s nothing really profound here to be honest, but when this clicked for me it felt momentous.

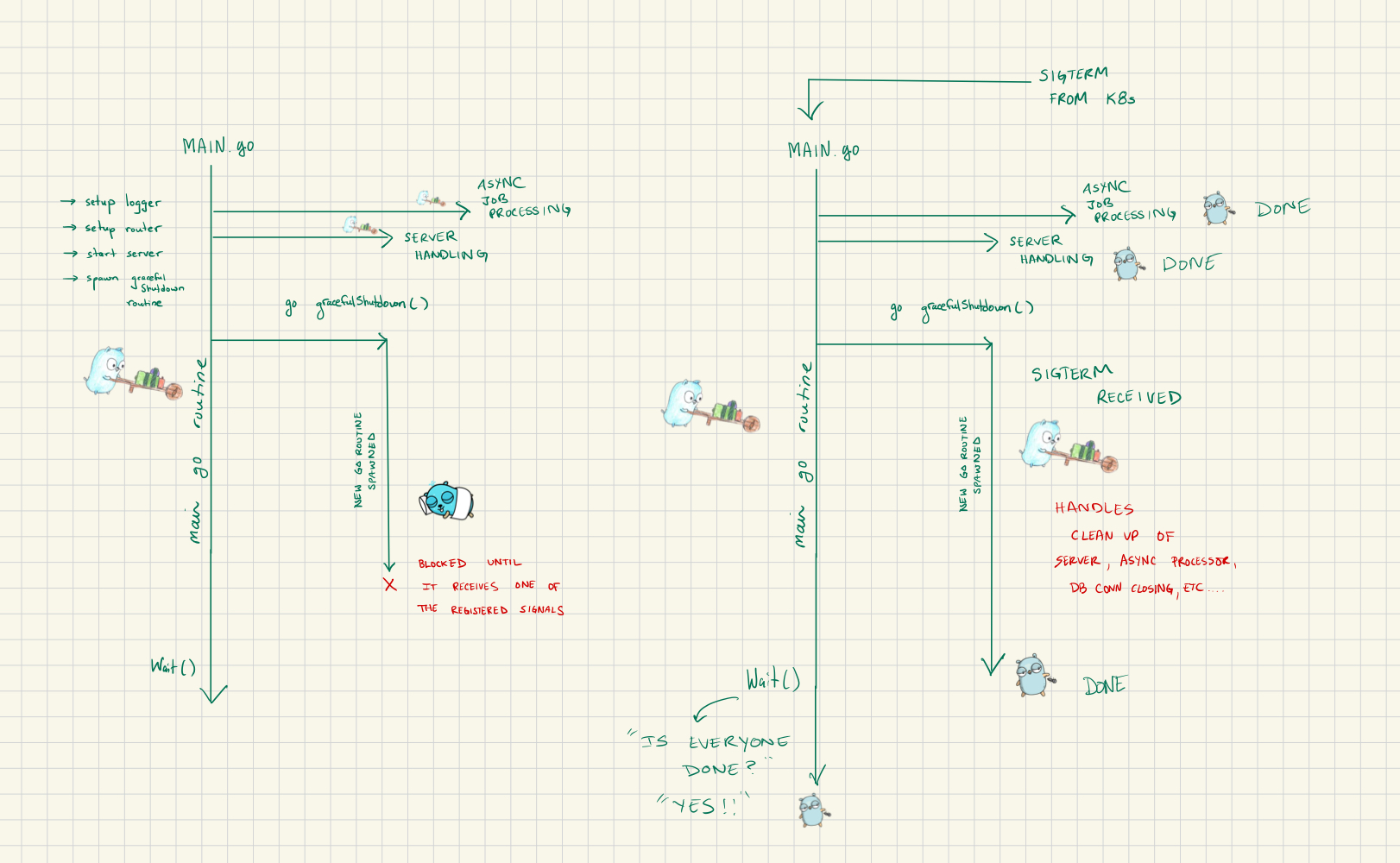

Thinking through concurrent code wasn’t intuitive for me, but visualizing the goroutine’s through diagrams helped me understand the state of the application. Here is a high level diagram for how we handle graceful shutdown in one of our Microservices at Teachable:

Our main goroutine spawns a few additional goroutine’s that will handle:

- Asynchronous job processing

- Initializing server / handling incoming HTTP requests

- Graceful Shutdown via listening for incoming signals (ie. SIGTERM, etc.)

These goroutine’s are responsible for communicating with each other and handling potential termination signals. In the use case shown above, once we receive the SIGTERM:

- Our

gracefulShutdownfunction receives and handles the signal in a similar way to this implementation here. - Before the function completes, it initiates the clean up process; including server shutdown, async job process shutdown, closing db connection, flushing logs, etc.

- The other goroutine’s are also listening for any sign of a cancellation that get triggered when calling the clean up function. For the server, that’s

httpServer.Shutdown. We use asynq for our asynchronous job processing and it has it’s own signal handler that initiates upon running the processor. - Once all the clean up work is complete, the goroutine’s finish running and the

.Wait()that’s called in the main goroutine stops blocking and the app exits successfully.

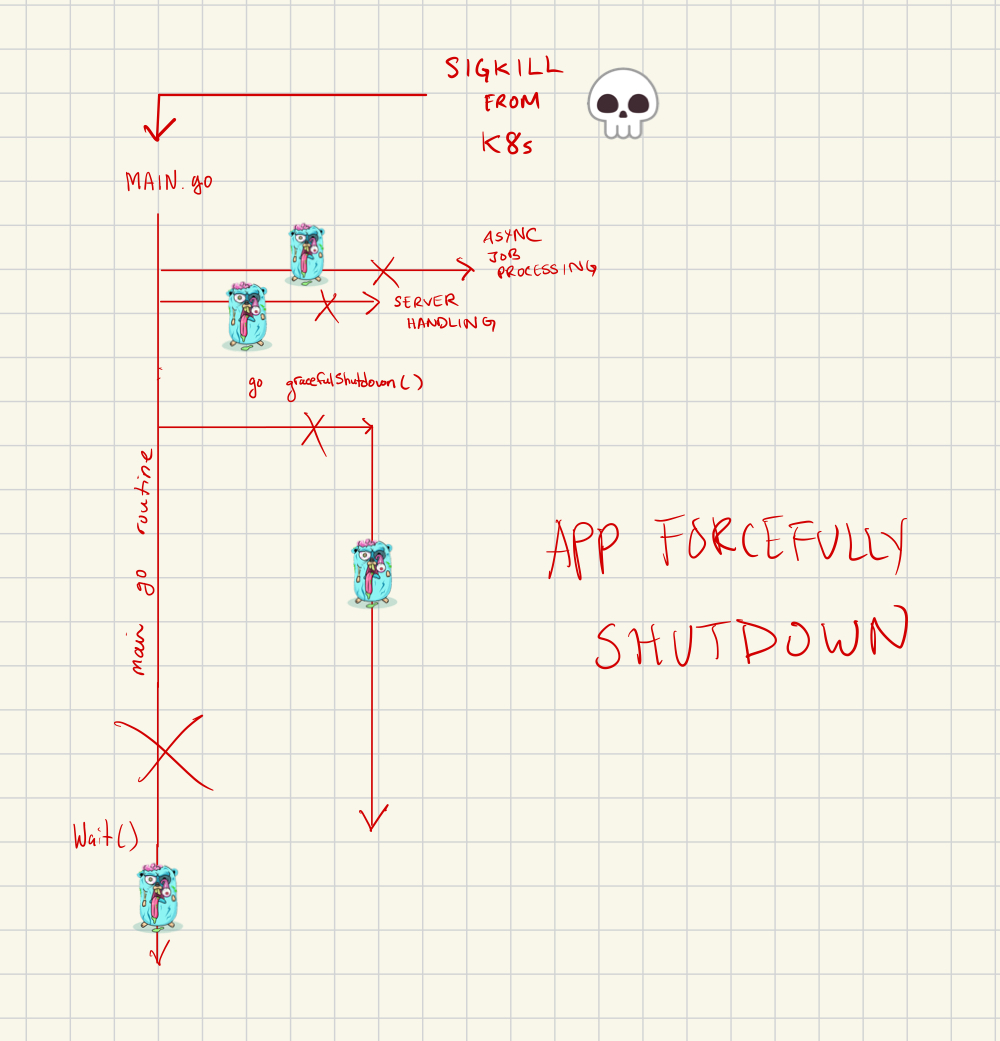

In the case of a SIGKILL you can imagine the following devastation:

Conclusion

In conclusion, Graceful Shutdown is an important aspect of a resilient and distributed application. Service interruption is inevitable when your application lives in a cloud environment, so building a robust application that handles failure gracefully ensures that our applications remain up and running while minimizing end user impact.